Contents

- The game

- Transparency

- Dealing with realism

- Peak oil

- Being the bad guys

- Management

- Demand and supply crisis

- Politics

- Imperialism

- Pseudo history and futurology

- Game Over?

- Selected sources

Appendix: Events

Economic model source code (actionscript .txt)

The game

Oiligarchy is a playable commentary on the oil industry. The player takes the role of an "oiligarch" managing the extraction business in the homeland and overseas and lobbies the government to keep the carbon-fossil based economy as profitable as possible. Oiligarchy can be considered an extended business sim/tycoon game since the player makes decisions and performs actions that are not always in the domain of business. This mixed gameplay is meant to highlight the intricate relations between war, politics, and energy corporations. The purely economical activities range from finding new oil fields to building extraction plants and managing resources. As domestic resources decline, the player is forced to expand their business in foreign countries to meet the demands of the market. The overseas operations could require the political or military support from the government and various crisis management actions.

Transparency

This document, written after the release of Oiligarchy, attempts to outline the major game design choices we faced and provide footnotes and additional documentation to the parts that reference real-world situations or events. Since the inception of the Molleindustria project we argue that game design is never an ideologically neutral process: games, as every other cultural product, reflect the designers' beliefs and value systems. And this is particularly visible in games that claim to “simulate” actual non-deterministic situations.

We want to stress this idea by proposing a sort of politically informed post-mortem in which we describe the odd challenges of producing social commentary into a playable form.

Video games are intrinsically opaque texts due to their double nature of source code and playable software. Certainly the source code is the strictest manifestation of the algorithm, but it is generally unavailable or unintelligible to the player. On the other hand, the executable software which is “activated” by the player's performance cannot be fully grasped due to the potentially infinite texts that can be generated by the same algorithm (see Lev Manovich principle of variability in The language of new media p.55) and the complexity of the software's hidden computations. There is no definitive way for the player to assess that a certain output is triggered by a certain input. Because of this opacity we feel committed to breaking apart and explaining in natural language the components of the game that constitute the socio-economic engine. We hope in this way to facilitate the textual analysis and the critique of the game, and, possibly push other producers of activist/political games to do the same.

Dealing with realism

Games referencing real-world elements and historical events are problematic cultural artifacts. Software does not constitute a document itself as a documentary footage or a journalistic report. Games often feature carefully reproduced elements such as characters, vehicles, and weapons, however the way these elements operate and relate to each other via the gameplay is always dictated by an algorithm that cannot be directly related to any actual entity (in the way, for example, a picture or a film have and direct, indexical relationship with objects in time and space). It is possible to create credible representations of phenomena that are already formalized into sets of rules (e.g. physical models), but when it comes to social systems or, more in general, human behavior our programming languages seem to be inappropriate tools.

Despite that, mathematical models constituting the core of a game can be based on documents or derived from well-informed theories. Obviously the goal has not been to produce some kind of scientific, objective representation, but to outline a web of cause-and-effect-relations that can arguably share strong qualitative similarities with the mess we call reality.

Peak oil

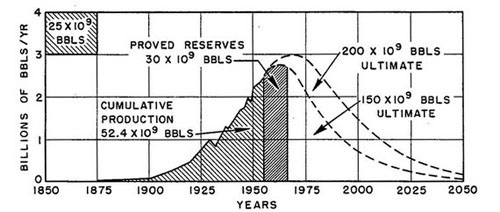

Oiligarchy’s main mechanic is loosely based on the Hubbert peak theory. The theory can be summarized as follows. For any given geographical area the rate of petroleum production tends to follow a bell-shaped curve. Early in the curve the production rate increases due to the discovery rate and the addition of infrastructure. Late in the curve the production declines due to resource depletion. Peak oil activists (sometimes called depletionists) argue that if global oil consumption is not mitigated before the peak, the availability of conventional oil will drop and prices will rise causing catastrophic chain reactions on the whole economy.

Original prediction of domestic production peak by M. King Hubbert

Oiligarchy is meant to popularize Peak oil as a key issue to understand present and future crisis and to contribute to the re-framing of the vague and deceptive argument of "dependency of foreign oil" that is dominating the current political discourse in the US.

We choose to focus on the United States because it is the most oil dependent country, where the relations between politics and the oil industry played a major role in recent times and despite the relative decline of the American global influence, US policies are going to affect the rest of the world for many years to come.

Sources: Peak Oil

Being the bad guys

As Molleindustria's McDonalds' video game, Oiligarchy places the player in the shoes of the "bad guys" in order to articulate the critique. Our belief is that power structures can be understood more clearly if represented from a privileged position. The player tends to perform actions with both positive outcomes (profits, advancement in the game) and social or environmental costs (a.k.a. negative externalities) dealing with responsibilities in a system that does not really punish unethical choices. The unethical gameplay is designed to reflect the free market system, which is ultimately, the object of the critique.

Moreover, a mirrored point of view can avoid the trap of the “simulated activism”, a cathartic illusion of empowerment and normative “do the right thing” enunciates. Games do not work as Skinnerian conditioning devices: games rewarding (virtual) social change do not produce activists for the same reasons games rewarding (virtual) violence do not produce violent players. As a result of taking a look at the players’ feedback, it is apparent that pushing the people to explore the dark side, especially if done with abundant irony, does not undermine the overarching game objectives.

Management

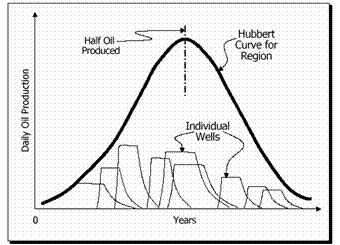

Although the player is intended to lead a big vertically integrated oil company, the game only shows the beginning of the production chain, as well as exploration and extraction, which is the relevant part for addressing the issue. The visual representation of drilling and extraction is grossly simplified, but on the other hand, an important and not broadly known technical detail is taken into account: the extraction rate of every single oilfield tends to gradually decline when the reservoir is half depleted. This is one of the factors that determines the typical bell shaped curve of oil production.

Hubbert curve, regional Vs Individual Wells. Source ASPO

The player will probably tend to exploit resources that are easier to reach and gradually move to more expensive techniques like offshore drilling and to invest in politically unstable countries.

The bell shaped curve of production is the most counter-intuitive part of the Peak Oil theory: unlike a car that suddenly stops working when the tank is empty, the global crude extraction (in a business as usual scenario) reaches the peak when half of the oil underground remains. Then it declines gradually, but at progressively increasing speed like a roller coaster slope.

This factor deeply affects a typical game session that will have an expanding phase (as in all the mainstream strategy and business simulation games) followed by a contracting phase marked by the struggle to keep up with the demand and the convulsions of the economic system.

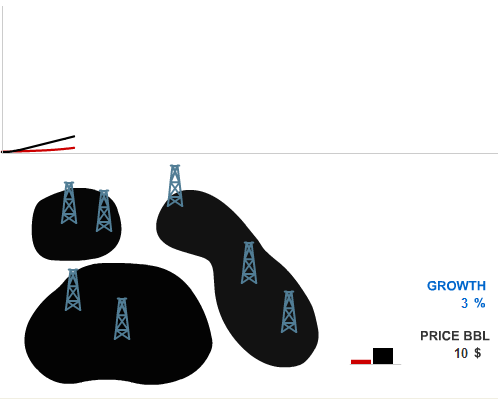

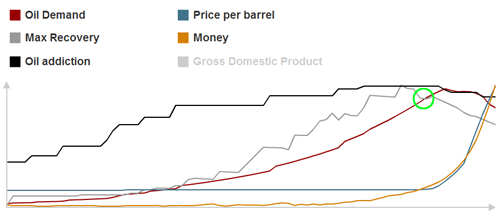

Early Oiligarchy prototype representing the peak dynamic. Click to start and click on the black fields to build wells. The red line is the demand the black one is the maximum production.

Demand and supply crisis

The player's primary objective is to match the market demand of crude. The demand is a function of two variables: the Gross Domestic Product (representing the size of the economy) and an umbrella value called “oil addiction”.

GDP tends to grow at a rate of 3% per year, which is a reasonable rate for the game's time frame.

The figure can be lower or even negative (recession) in case of serious oil supply crisis or event-generated crisis (see events in Events Appendix).

The “Oil addiction” variable is as homage to George W. Bush ghost-writers, who popularized the expression in a rare moment of honesty, and represents the dependency of the entire economy to fossil fuels. This takes into account a wide range of factors such as agriculture, public transportation, car-centered urban planning and so on.

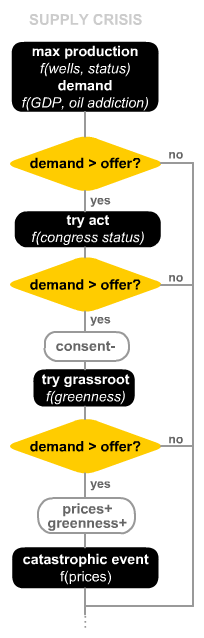

When at the beginning of the turn/year, the oil production is lower than the demand a supply crisis algorithm is triggered. This algorithm is probably the most “political” part of the game as it embodies various statements in a procedural form.

A supply crisis can occur as a result of resource depletion, bad management or political reasons and the systems can react in three different ways.

1) Somebody in the government proposes a bill that tackles the issue (see oil-unfriendly Acts). Oil-unfriendly Acts generally tend to moderate the demand by reducing the oil addiction. The probability for these types of acts to be approved, depends on the government “oiliness” (see politics): with a fully oiled government all the “good” acts are basically blocked, while with a fully green government, every year of crisis a new act should be approved. Every act has a degree of “boldness” that also plays a part in the approval. For instance, an act that promotes electric cars is bolder and less likely to be approved by an ideologically mixed administration than an act which simply reduces speed limits to save gas.

2) If the bill is not approved or the act is not sufficient to solve the oil deficit, the government popularity decreases and the social body tries to react with initiatives that in the game are classified as grassroot (see grassroot). These initiatives are more likely to happen if the society has a high of environmental awareness (greenness).

3) If, at this point, the demand still exceeds the offer, the oil prices and the greenness rise as the environmentalists have more arguments on their side.

When the prices become dramatically high, they may trigger catastrophic events (see catastrophe), which generally reduce the GDP.

Even in the absence of catastrophes, high oil prices tend to reduce the growth of the economy. After a crisis, oil prices will gradually recover to the previous stable value.

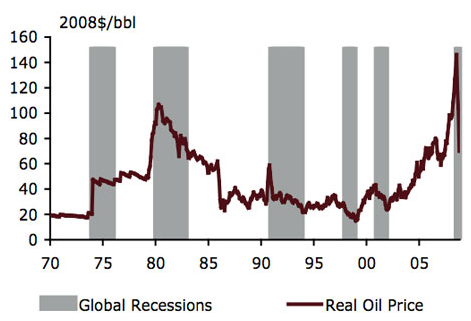

Graph linking recession and oil prices. Source: What is the Real Cause of the Global Recession?

Politics

Affecting the politics is the key to being a successful manager in Oiligarchy. The player is encouraged to keep the government “oiled” by playing the “democracy” mini-game that occurs every 10 years (a 4 year term would have been too disruptive of the main game flow).

The democracy mini-game refers to a type of election race, but it does not try to simulate the complexities of the electoral process. The donations during the race should be seen as a representation of the corporate influence on politics in a broader sense, including lobbying, revolving doors and so on.

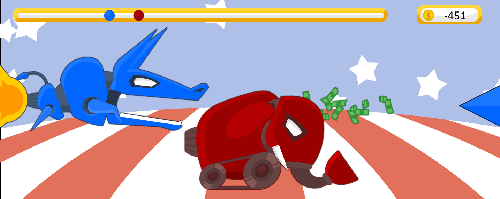

The depiction of the two parties as interchangeable, bulimic, money-burning machines is both a satire of the overstated spectacle of the U.S. presidential campaign and an ironic response to the so-called “political games” simulations of the presidential campaigns that reinforce the widespread deceptive equation: politics=elections.

The initial speed of the two parties reflects the popularity of the last administration which is, in turn, dependent on a generic citizen satisfaction (consent) and environmental consciousness which are visualized in the Washington scenario as demonstrators.

Additionally, there are some random thrusts that can affect the race and are meant to represent variables like the effectiveness of the campaign and the typical scandals and surprises involving the two parties.

The ability of the player to affect the election outcome is very limited, but his donations have a fundamental influence on the policies of the future administration.

As a part of the satire, the two parties have no ideological features, in other words the Republican Party is not intrinsically more inclined to help the oil industry or vice-versa (observing the electoral funding by industry you can notice a general preference for Republican, but oil and gas industries are not amongst the most partisan industries.

Therefore, the experienced player would simply choose to “bet” on the winning party to obtain the most influence. These design choices loosely reflect a study by Steven D. Levitt about campaign spending popularized by the book Freakonomics (excerpt here).

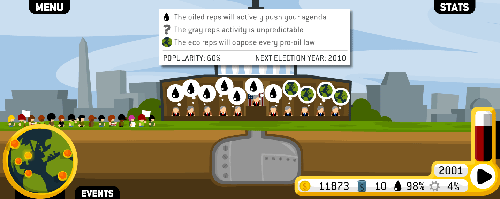

As a function of the result of the elections and the donations to the two parties, the government (a stylized rendition that summarizes the many institutions in a 10 people congress) will be composed by three categories of representatives:

- Oiled: representatives that will vote for oil-friendly bills (see oil-friendly acts) every year and oppose the oil-unfriendly bills.

- Green: representatives that will vote for oil-unfriendly acts in case of supply crisis.

- Gray: representatives that will vote for both kinds of bills with a probability of 50%.

The number of green representatives is directly related to the greenness: with the emergence of the environmental awareness (due to global warming or oil crisis) the green representatives will substitute the gray ones.

Big and “wise” donations can affect politics to elect an oil-friendly president. This will grant the player the possibility to access the secret underground room (a reference to the presidential cabinet and the Pentagon) and trigger “Special Operations”. Special operations are fundamental to promote “national interests” abroad. For instance, they will allow the player to invade Iraq and unblock its resources or to prevent or counter a potential nationalization of the industry in Venezuela (see special operations).

Imperialism

As domestic resources deplete, the player will be forced to explore and deploy wells in foreign countries. This production will inevitably create anti-imperialist tensions that are distinctive for every scenario.

Venezuela

In Venezuela the dissent will be initially led by indigenous natives, but as the exploitation continues, the whole government will struggle for economical autonomy. The path to independence is represented by various events and leads to the nationalization of oil industry, a move that blocks the player's wells and any further actions within the scenario. The nationalization can be prevented or reverted by an escalation of increasingly aggressive special operations culminating with a coup.

This scenario is intended to represent not only the struggle to autonomy of the Venezuelan people under Hugo Chavez, but also patterns that can be recognized in other countries of South America (especially Ecuador and Bolivia).

Sources: Venezuela

Nigeria

The Nigerian scenario has an extra menu representing the government which allows the player to deal with the dissent. The dissent will tend to follow a two-phase dynamic. The first phase sees the uprising of the Ogoni people and it assumes the form of peaceful blockade. The second phase is the emergence of armed groups and can either be ignited after years of exploitation, or indirectly triggered by the player's ruthless response: the government-assisted assassination of Ogoni activists (as it arguably happened in reality).

Sources: Nigeria

Iraq

Iraqi relations with Western countries have always been inconstant since the end of the British mandate and the game, in its initial post-WWII state, is quite inaccurate since it reflects a more recent situation.

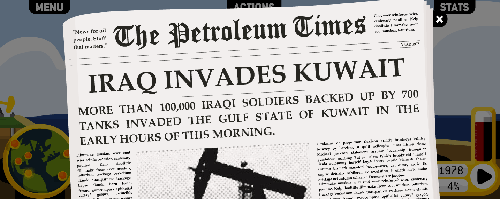

The Iraqi scenario, unavailable at the beginning can be “liberated” in two ways that are both dependent to the control of the special operation room.

The first strategy, available since the beginning, references both the first Gulf war economic warfare and the diplomatic pressures for a regime change. Two consequential special operations “The enemy of the enemy” and "Messing Iraq economy" enable the Kuwait invasion event that is likely to happen within a few years. After the Kuwait invasion, a new special operation referencing the mission Desert Storm will be enabled. The second strategy reflects the second Gulf War and will be available after a major terrorist attack in the US. It requires the manufacturing of a link between terror and Iraq (that is, another special operation called "WMD").

In case of successful war, both cases will lead to a similar outcome: the unblocking of the scenario action menu. However, after a period of relative stability the insurgency movements will start to target oil wells and occupation forces. Attack on wells can be countered by hiring mercenaries (a reference to Blackwater) to protect structures.

Attacks to the main base in Baghdad can be contained by sending more troops, and ordering a "special operations" that, as a side effect, reduces the popularity of the administration.

Successful insurgent victories against the occupation forces will block plants and any further action in Iraq until another re-liberation.

Sources: Iraq

Pseudo history and futurology

Oiligarchy is an ambitious game: it tries to describe how the USA became addicted to oil, how it could have been different, and how a successful or a failed transition to a post-carbon society would look like. So we chose to start from the WWII aftermath, that is arguably the beginning of the golden age of oil for the combined effect of the Green Revolution, the car culture and

the suburbanization.

Since the game statements revolve around the major role of the oil industry in shaping the world we live in, we had to give the player the possibility to affect the history but, at the same time, we wanted to provide some incentives to retrace the events as they actually happened to stimulate a critical reading of history.

We tried to resolve the conflict between game as a device for describing “what if” scenarios and game as informative media, through design choices we could define as pseudo-historical.

Oiligarchy pseudo-history is based on a procedural interpretation of past. In-game events do not occur on a certain year because that is what happened in reality, but they are entangled in a web of cause and effect relations. Every event is enabled by certain conditions (game variables, players’ actions or other events) and produces certain effects. Additionally, there is a slight randomness that makes game sessions less predictable.

Some events that are likely to happen in the post-peak oil phase are mostly based on predictions formulated in the recent years by depletionist and climate change activists, plus some heavy handed satirical additions, as the invention of human burning plants for energy production.

Though they may have similar outputs, events are classified in many ways:

- Oil-friendly Acts: approved roughly every 3 years according to the oiliness of the governments and their “shameless” value.

- Oil-unfriendly Acts: proposed every year and approved according to the oiliness of the governments and their “boldness” value.

- Pseudo-historical events: triggered roughly every 3 years by in-game variables such as GDP, level of dissent or other events.

- Grassroot initiatives: activated according to the society environmental awareness and their greenness value.

- Catastrophe: triggered by high oil prices in years of unsolved supply crisis.

- Undercover Operations: enabled by in-game variables with certain “escalation” patterns, but directly triggered by the player in case of oiled President.

- Nigerian Government: triggered by the player.

For a complete list of events, how they affect the game variables and detailed documentation see the appendix Events.

Challenging Meaningful Play

The contemporary science of game design revolves around the idea of meaningful play. According to Salen & Zimmerman (see Rules of Play, unit 1), players should be given opportunities to take non-random actions and make decisions that have an immediately clear and integrated (makes "big-picture" sense) effect on the game.

Meaningful game systems are elegant, appealing, easy to understand and internally consistent. Unfortunately, such kinds of games may be inappropriate to describe systems that are inelegant, unappealing, obscure and contradictory like the free market capitalism that is destroying the world.

Oiligarchy is full of broken connections, meaningless interaction, inverted rewards and randomness. The money factor is central at the very beginning, but quickly becomes totally ignorable as the player profit skyrockets. The administration popularity represented by the demonstrators in Washington is presented as a sort of punishment or a bad performance warning, but it does not meaningfully affect the player routines since, in the eyes of the oiligarch, the parties are interchangeable. In the late stages of the game, donating money to the parties may be a counter-productive habit because there are no more oil-friendly acts left and the prices are rising anyway. Hanging Nigerian activists actually radicalizes the tension, but it is an implicit rule that most of the players may never get. And, above all, the very same goal of the game becomes quite blurred after the peak.

Game Over?

Oiligarchy has four possible endings.

In the pre-peak phase the player can be fired for bad management if the demands exceed the offer for too many years. That is an implementation of the free competition mode of production. Competition is not directly simulated for the simple reason that it never played a major role in the history of oil industry, nevertheless if the player tries to create too much artificial scarcity or refuses the expansion imperative he/she will be kicked out of the market.

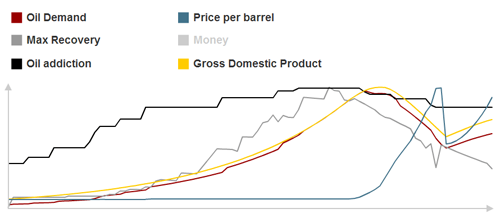

Game statistics after the peak. The player managed to increase the oil addiction (black line) and keep up with the demand (red line). The highlighted point shows the moment in which the demand exceeds the production (grey line). Prices skyrocket and some grassroot initiatives are trying to reduce the addiction.

The hardcore gamer will probably see the Mutually Assured Destruction ending that represents the failed transition to a post-carbon society. This global nuclear war scenario happens when the oil prices reach the ceiling of $300 per barrel and it is usually the result of aggressive and persistent efforts to control the government. By buying off the politicians, the player essentially introduces rigidity in the system and prevents a harmonic rearrangement of the society.

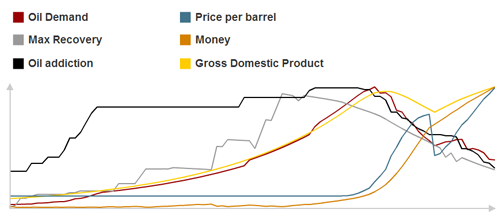

An example of game ending with MAD. After the peak (grey line declines), the government is still oiled and no act reducing the oil addiction (black line) is approved. The addiction and consequently the demand is reduced by grassroot initiatives at first and then by an economic crisis (yellow line). Since the reforms are still blocked a reprise in GDP growth and the declining resources causes another spike in prices that triggers the M.A.D. end screen.

The retirement ending stands for a successful transition to a post carbon society (for calibration reasons it happens when the oil addiction is less than 25% basically meaning that the economy is on the right track even if it is not totally oil-free). Retirement usually happens when the player loosens the grip on politics around, or after the peak oil. It is basically the happy ending, though it can be reached after some major catastrophes.

- This is basically an implementation of our conclusions and hopes. In brief, we believe that the dependency on oil can be solved by a combination of different approaches:

- A series of top-down, government-lead structural policies ranging from supporting renewable energies to nation-wide infrastructural rearrangement (see oil friendly acts in the Events Appendix).

A proliferation of bottom-top, more or less organized initiatives promoting alternative lifestyles such as the rejection of consumerism, promotion of bike transportation and organic, locally grown farming (see grassroots Events Appendix) - A substantial downsizing of the economy on the whole and the overcoming of the GDP growth imperative.

An example of game ending with Retirement. After the peak (gray line declines) the player stop affecting politics. A series of acts and gressroots initiatives reduce the oil dependency (black line) and consequently the demand (red line). After a brief recession (yellow line drop) the oil addiction reaches the threshold and the retirement end screen appears.

The fourth possible ending is titled Farewell West and represents a mildly dystopic collapse of western civilization as we know it. It occurs when the GDP goes below a certain level, three times the initial value. Apparently the fourth ending never occurred to anyone and may be actually impossible to reach.

At the end of the day good gamers tends to get rich and blow up the world while the bad, lazy or non competitive gamers may reach a tragic end. The debasement and relativization of the binary win/lose formula seems to be the most shocking part for the habitual gamers. The online feedback shows how the players are struggling to negotiate between the ambiguous rewards and punishment system and the conventions they learned from traditional strategy/business games. Many players posted successful tips for reaching the dystopic scenario with the most money, others proposed counter-strategies about how to get to the happy ending. Some people argued that the best way to “beat” the game is to avoid any imperialist activities while others suggested building as many human burning plants as possible.

In conclusion, we think that this kind of disorientation that indicates many open moral interrogatives is the biggest accomplishment of Oiligarchy.

Selected sources

ASPO, The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas

The Oil Drum, Discussions about Energy and Our Future

|

|

|

The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies

by Richard Heinberg |

The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-first Century

by James Howard Kunstler |

|

Crude impact , documentary

|

The end of suburbia, documentary

|

More in the Event appendix

Venezuela

Amazon Watch, video and documents about Oil industry devastation in South AmericaPINR, Venezuela Moves to Nationalize its Oil Industry

Venezuela Analysis, The Nature of CIA Intervention in Venezuela

Minimizing Mischief in Venezuela, Stabilizing the U.S. Oil Supply, a proposal by the right wing think tank Heritage Foundation

Eva Golinger, The Chavez Code:Cracking U.S. Intervention in Venezuela

The Guardian, Venezuela coup linked to Bush team

More in the Event appendix

Democracy Now, Drilling and killing, award winning audio documentary about Chevron's role in the assassination of Nigerian people.

Human Right Watch, The ogoni Crisis, A Case-Study Of Military Repression In Southeastern Nigeria (recently removed from the official website)

Oil War, Nigeria, a documentary about Nigerian emancipation movements.

Naomi Klein, Shock Doctrine, Part 6. Chapter linking free market policies and iraqui insurgency.

Cronology of relations between US and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI)

Economic moves that lead to the Kuwait invasion

Salon, Bush knew Saddam had no weapons of mass destruction

More in the Event appendix