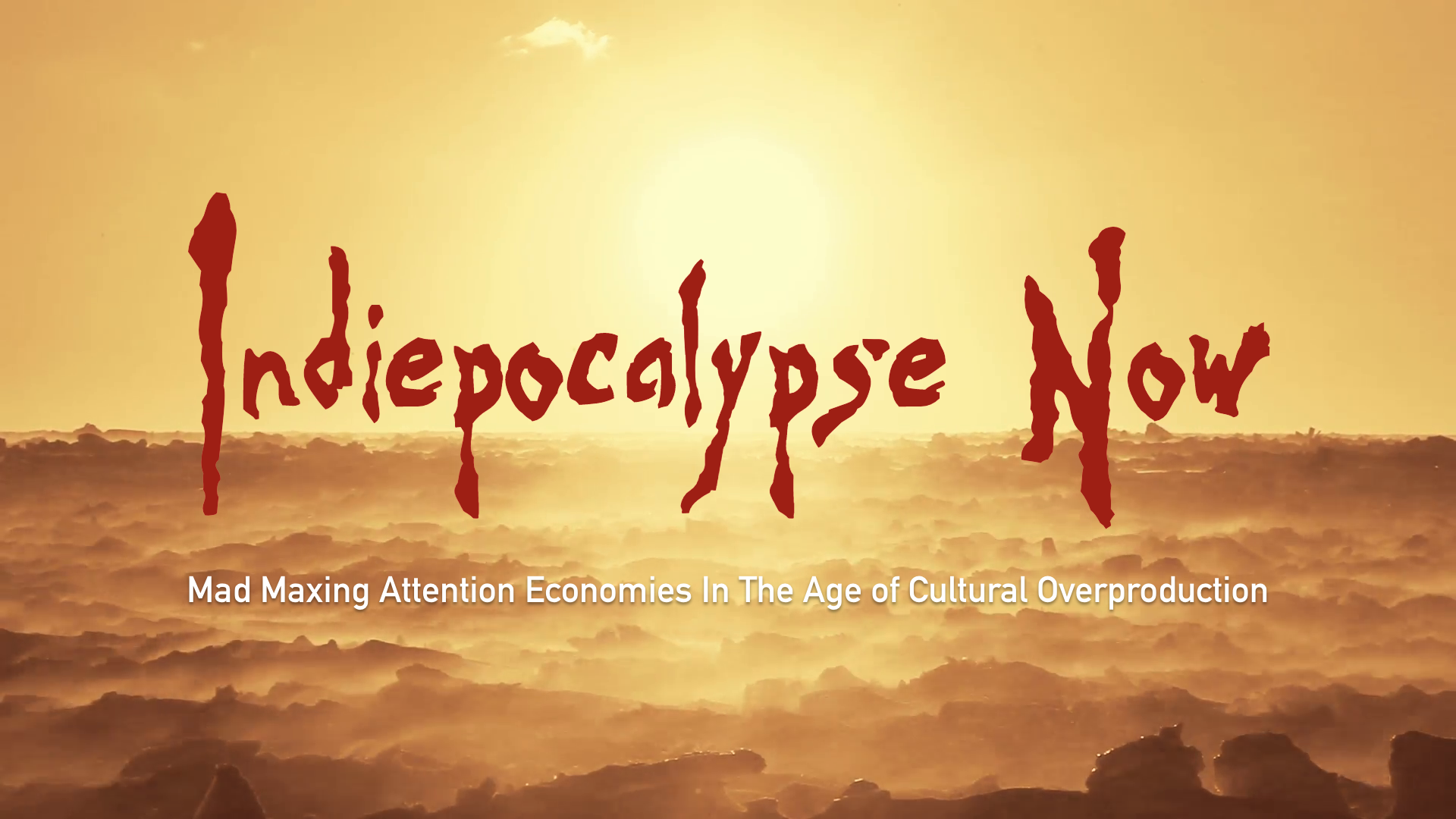

Today I want to talk about a dilemma that all cultural producers are facing now.

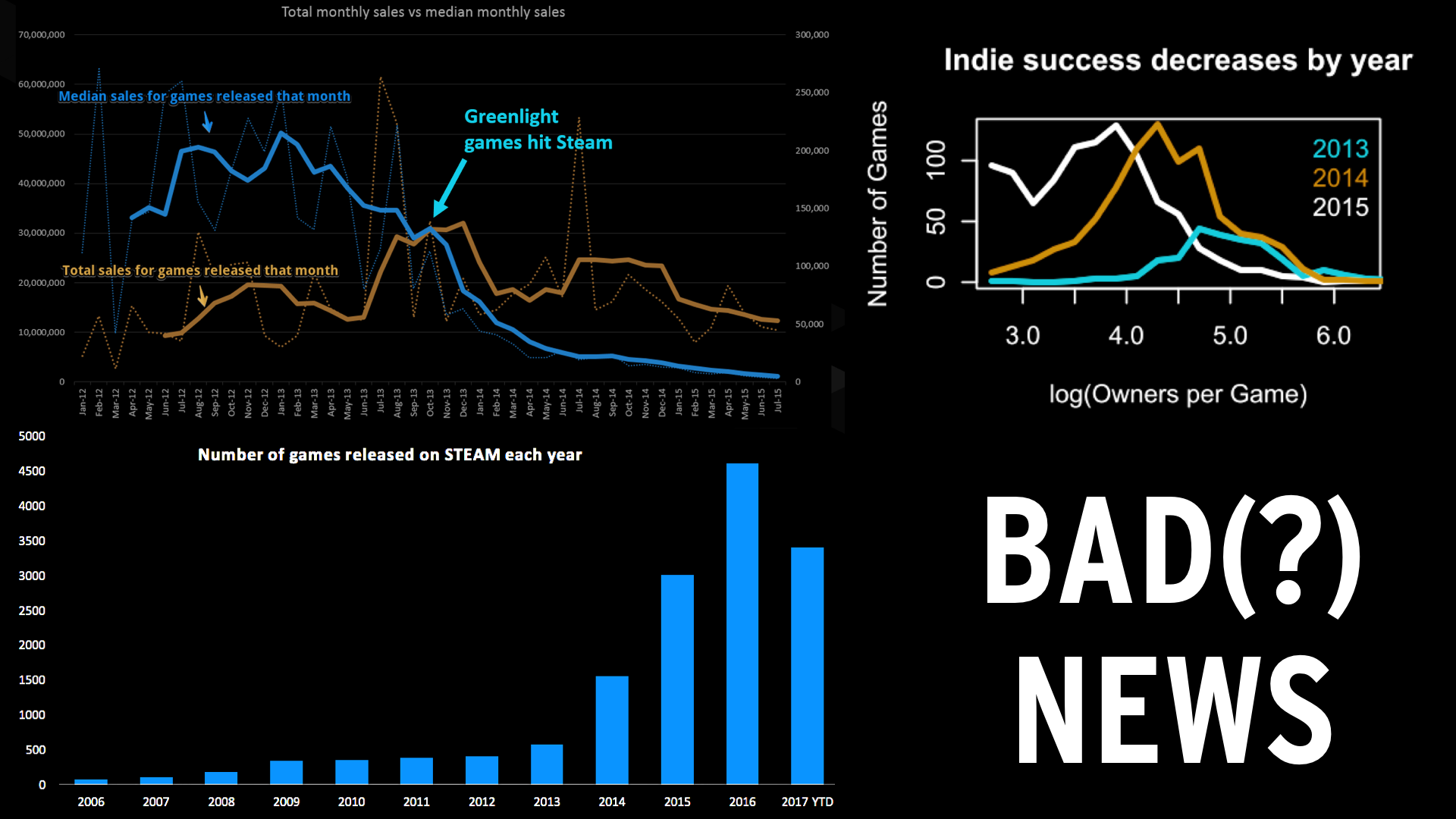

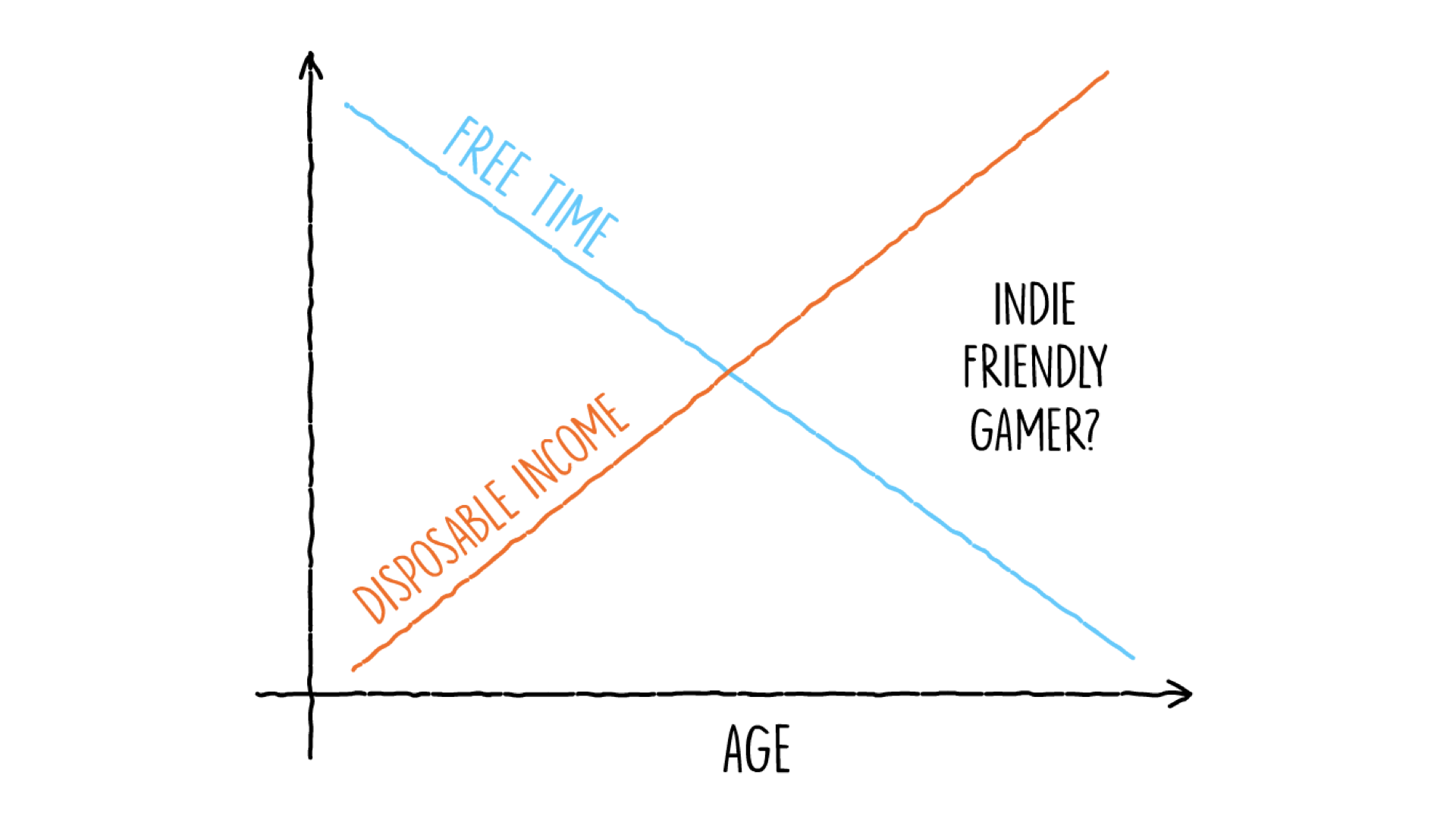

In gaming circles it is referred as the Indiepocalypse.

How to deal with a saturated, financially unsustainable market for indie games?

How can we maximize the developers happiness without reducing the diversity of voices?

Disclaimer: This is a fake business talk, I don’t make commercial games and I’m not even good at selling my free stuff. But as a teacher I constantly have to think about what kind of markets and contexts my students will face when they graduate.

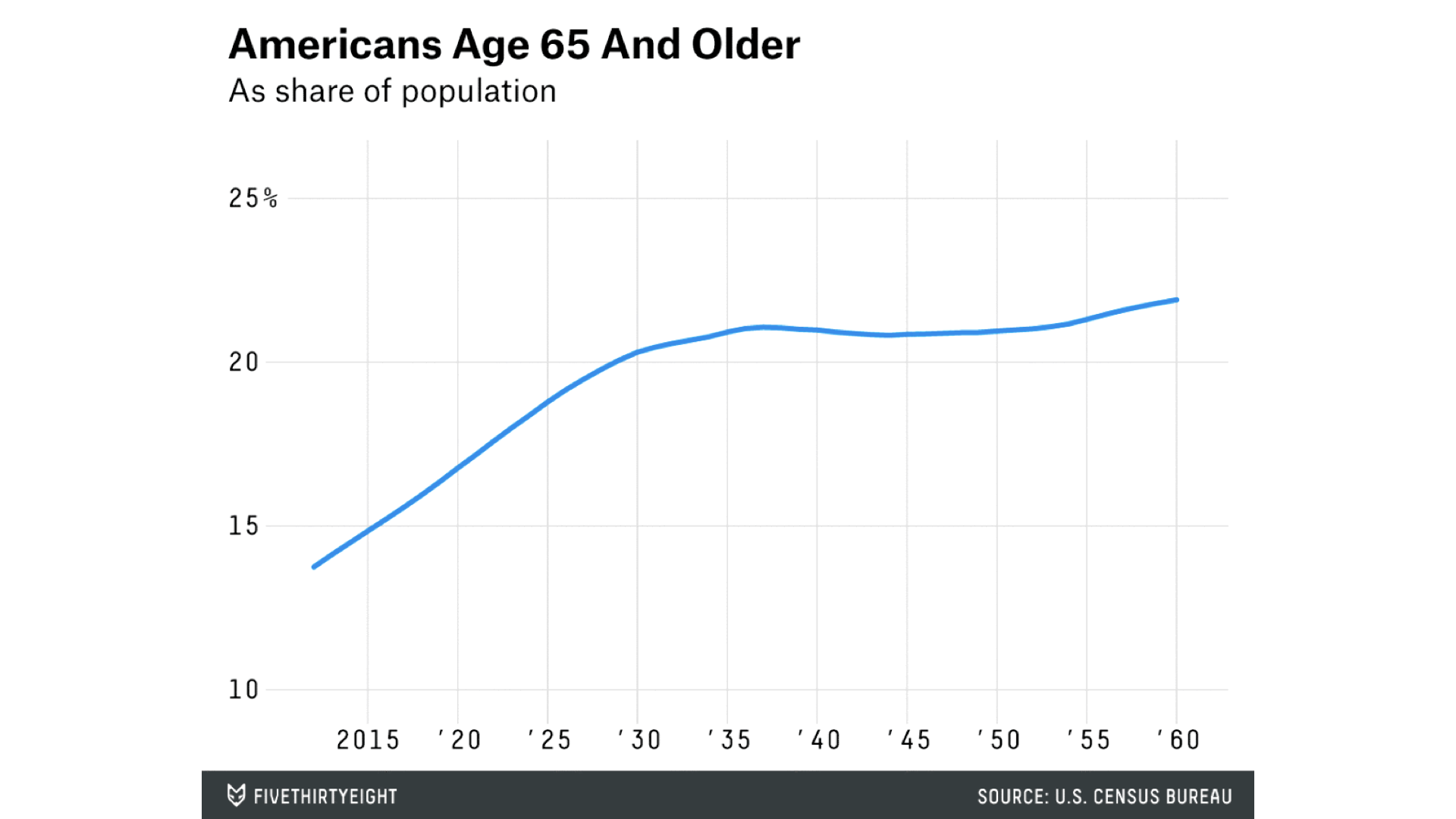

Let’s start with the good news.